Effective Note-Taking Methods for Retaining Complex Research Concepts

In an era of information overload, the ability to retain and meaningfully process complex research concepts has become a critical academic skill. Students and early-career researchers are no longer struggling to access information; instead, they face the challenge of organizing, understanding, and remembering it. Effective note-taking sits at the intersection of comprehension and long-term retention, acting not as a passive record of information, but as an active cognitive tool that shapes how knowledge is processed and recalled.

The Cognitive Purpose of Note-Taking: From Recording to Thinking

At its core, note-taking is not about transcription. Decades of cognitive research show that simply writing down information verbatim produces limited learning gains. The true value of note-taking lies in its role as a form of generative processing—the mental effort required to select, organize, and rephrase information in one’s own words.

When learners take notes effectively, they engage in what psychologists call elaborative encoding. This process strengthens memory traces by linking new information to prior knowledge, creating multiple pathways for recall. For complex research concepts—such as theoretical frameworks, methodological debates, or interdisciplinary models—this active engagement is especially important. These ideas cannot be memorized in isolation; they must be understood as part of a larger conceptual system.

Historically, note-taking evolved alongside scholarly practices. Medieval scholars annotated manuscripts to interpret dense philosophical texts, while early scientists kept detailed research notebooks to track hypotheses and observations. In both cases, notes functioned as thinking spaces rather than mere summaries. Modern learners face a similar challenge, but with exponentially more information and far fewer natural pauses for reflection.

A common mistake is treating note-taking as a neutral or mechanical task. In reality, the structure and format of notes influence how information is mentally organized. Linear notes tend to reinforce sequential thinking, while visual or relational formats support systems thinking. Understanding this distinction is key to choosing methods that align with the nature of complex research material.

Linear, Visual, and Conceptual Approaches: Strengths and Limitations

Traditional linear note-taking—outlines, bullet points, and summaries—remains widespread for good reason. It works well for structured content such as lectures with clear progression or articles with a strong argumentative flow. Linear notes help learners track definitions, steps, and hierarchical relationships. However, they often struggle to capture non-linear relationships, competing theories, or feedback loops common in advanced research.

Visual approaches address this limitation by externalizing relationships that are difficult to express in text alone. Mind maps, diagrams, and flowcharts allow learners to see how concepts connect, overlap, or diverge. For example, when studying a complex research field such as cognitive neuroscience, a visual map can show how experimental methods, theoretical models, and ethical concerns intersect. This spatial representation reduces cognitive load by making abstract relationships concrete.

Concept maps go a step further by explicitly labeling relationships between ideas. Unlike mind maps, which often radiate from a central concept, concept maps use linking phrases to define how elements relate to each other. This makes them particularly effective for retaining complex theoretical frameworks, where understanding depends on grasping precise relationships rather than isolated facts.

Despite their advantages, visual methods are not universally superior. They require time, practice, and a certain level of comfort with abstraction. For learners unfamiliar with a subject, attempting to map concepts too early can lead to confusion rather than clarity. This highlights an important cause-and-effect relationship: the effectiveness of a note-taking method depends not only on the material, but also on the learner’s prior knowledge.

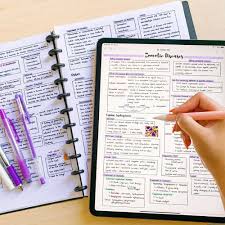

In practice, the most effective strategies often combine linear and visual elements. A student might begin with structured notes during initial exposure, then transform those notes into diagrams or concept maps during review. This transformation itself becomes a powerful learning activity, reinforcing understanding through reorganization.

Digital Tools and the Myth of Efficiency

Digital Tools and the Myth of Efficiency

The rise of digital note-taking tools has fundamentally changed how students interact with information. Applications that support tagging, hyperlinks, multimedia, and search functions promise greater efficiency and flexibility. For complex research concepts, these tools offer clear advantages: they allow learners to connect notes across courses, link primary sources directly, and update ideas as understanding evolves.

However, digital convenience comes with cognitive trade-offs. Typing encourages speed, which can lead to shallow processing and verbatim transcription. Studies comparing handwritten and typed notes consistently show that handwriting promotes deeper understanding, precisely because it forces selectivity. When learners cannot write everything down, they must decide what matters.

This does not mean digital tools are inherently inferior. Their effectiveness depends on how they are used. Digital note-taking becomes cognitively valuable when it supports active manipulation of information—such as restructuring notes, embedding questions, or linking concepts across documents. The danger lies in mistaking accumulation for comprehension. A perfectly organized digital archive is useless if it is never revisited or mentally processed.

Another overlooked factor is attentional fragmentation. Digital environments make it easy to switch between sources, notes, and unrelated distractions. For complex research concepts that require sustained focus, this fragmentation undermines deep processing. As a result, some learners adopt hybrid systems, combining handwritten notes for initial learning with digital tools for long-term organization and synthesis.

The broader lesson is that technology does not replace cognitive effort. It amplifies existing habits, whether productive or counterproductive. Effective note-taking remains a skill, not a feature.

Applying Note-Taking Methods to Complex Research Material

Complex research concepts differ from introductory material in one crucial way: they are often ambiguous, contested, and evolving. This requires a shift in note-taking goals—from capturing “what is true” to tracking how ideas relate, differ, and develop over time.

One effective strategy is question-driven note-taking. Instead of organizing notes around topics alone, learners structure them around research questions or problems. This mirrors the logic of academic inquiry and helps retain not just information, but relevance. For instance, rather than listing theories, a student might ask how each theory explains the same phenomenon differently.

Another powerful technique is comparative structuring. When notes explicitly compare methods, models, or arguments, they encourage evaluative thinking. This is particularly useful in fields where multiple perspectives coexist, such as social sciences or interdisciplinary research. By embedding comparison directly into notes, learners reduce the need for later reorganization.

Regular synthesis is equally important. Complex concepts cannot be retained through one-time exposure. Periodic synthesis—rewriting notes into summaries, diagrams, or teaching-style explanations—strengthens long-term memory. This process aligns with the testing effect and retrieval practice, both of which are well-supported by cognitive science.

Finally, effective note-taking acknowledges uncertainty. Instead of forcing premature clarity, good notes capture open questions, doubts, and contradictions. This practice not only reflects the reality of research, but also keeps learners intellectually engaged. Notes become a living document rather than a static record.

Table: Comparing Note-Taking Methods for Complex Research Concepts

| Method | Best Use Case | Cognitive Benefit | Main Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Notes | Structured lectures, definitions | Clarity, hierarchy | Weak at showing relationships |

| Mind Maps | Exploring broad topics | Visual association, memory cues | Can oversimplify complex ideas |

| Concept Maps | Theoretical frameworks | Relational understanding | Time-intensive to create |

| Handwritten Notes | Initial learning | Deep processing, retention | Harder to reorganize |

| Digital Notes | Long-term projects | Flexibility, connectivity | Risk of shallow processing |

Key Takeaways

-

Note-taking is a cognitive process, not a mechanical task.

-

Retention improves when notes require active selection and reorganization.

-

Linear and visual methods serve different cognitive purposes.

-

Digital tools are effective only when used to support deep processing.

-

Complex research concepts benefit from relational and comparative note structures.

-

Regular synthesis strengthens long-term understanding.

-

The best systems are adaptive rather than fixed.

Conclusion

Effective note-taking is less about finding the perfect method and more about aligning strategy with cognitive goals. For complex research concepts, notes must do more than store information—they must support understanding, comparison, and ongoing inquiry. By treating note-taking as an active intellectual practice, learners transform their notes from passive records into tools for thinking. In a knowledge landscape defined by complexity rather than scarcity, this skill becomes not just useful, but essential.

Leave a Reply